|

News Portal

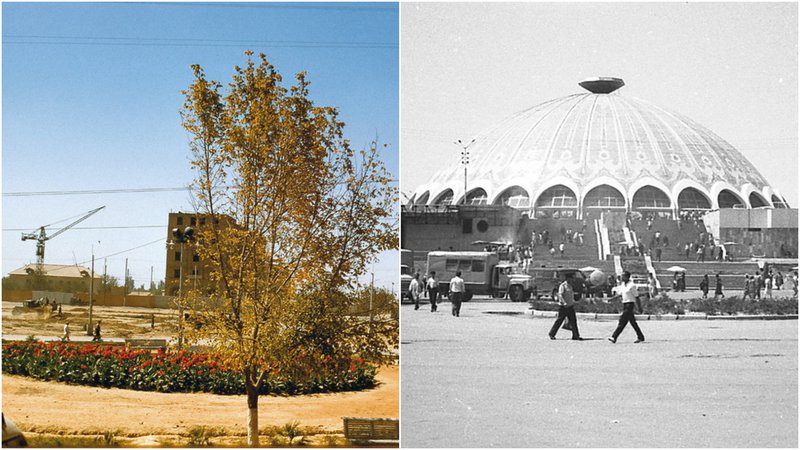

Uncontrolled urban development in Tashkent and elsewhere has led to the emergence of a vibrant, if perhaps fragile, civic mobilisation in Uzbekistan

|

For Zamanov and his neighbours, the decision in early 2018 to pull down their apartment block was nothing more than an outrage. Not only was House No. 45 a community unto itself, it is located near the remains of an ancient walled city, Ming Urik. In response, House No.45 transformed into an informal organisation, with residents turning their homes into its various campaign departments.

The block’s “legal department” attended three court cases and submitted over 15 appeals to various state institutions. The “human resources office” compiled lists of which residents wanted to stay and which wanted to leave. The “press office” gave interviews to local and international media, while the “research department”, in cooperation with foreign colleagues, collected information on the cultural and architectural importance of their home, and the “events management” office organised cultural gatherings.

In the end, Uzbekistan’s culture ministry awarded House No. 45 protected status. “House No. 45 is not only about the building, it’s about its residents,” says Zamanov. “We have known each other for decades, but without solidarity we could not have won.”

Today, people in other Tashkent neighbourhoods are organising to protect their homes from the onslaught of urban redevelopment that has gripped the Uzbek capital in recent years, pointing to the lack of protection from city institutions in the new Uzbekistan.

Today’s massive construction boom in Uzbekistan is the result of the economic transformation of the country since the death of president Islam Karimov 2016, which has resulted in the commodification of public space. Houses, parks, and cultural heritage are all affected.

The process is transforming the city’s identity in ways that many residents find unwelcome. Late Soviet architecture is famous for its boxy residential buildings, but a more important detail is that public infrastructure of the period was usually built close by, designed to be accessible and affordable (or even free) for locals.

The new brand of urban development prioritises consumption over other forms of behaviour. This is evident across the world, including many post-Soviet states, where luxury apartments, shopping malls, hotels, and business centres have replaced parks, more affordable homes, and even factories.

In turn, cities become sites of contestation and resistance, as various groups organise and demand a fairer distribution of space and resources. Some of these groups focus on a particular neighbourhood or site in the city, while others concentrate on a specific topic, like demolitions and forced evictions.

The Facebook group “Tashkent-DEMOLITION” is one of these communities. Much like House No.45, the group was initially set up to exchange information about demolitions and forced evictions in Tashkent, but it quickly morphed into an informal grassroots organisation with its own departments in charge of different issues. These include a legal office that provides online consultations, and attends court cases and press briefings by state institutions.

By way of example, group administrator Farida Charif tells me that activists attended court hearings in a case concerning the demolition of a 1930s apartment building in northwest Tashkent. The demolition was eventually cancelled.

“The mobilisation of residents and activists, as well as the local and international expert community saved the building,” Charif says. “It wasn’t an easy case but the residents were able to win in court and defend the building’s status as cultural heritage.”

“When I heard that the Independence Stele would be placed in Cosmonaut Park, I thought that Tashkent would lose another iconic place”

The popularity of these groups in Uzbekistan shows how people consider them reliable and independent organisations, contrary to formal institutions like the courts, the General Prosecutor’s office, and the city administration. These groups’ informal existence on social networks, like Facebook, Telegram and other e-platforms enables them to avoid bureaucracy, exchange information and mobilise faster, including to support one another. While some who fail to find support from formal bodies refer to these groups to increase awareness of their problems and search for support or advice, others use them as news platforms.

This was the case when Tashkent’s Cosmonaut Park, built in the centre of the city to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Vladimir Lenin’s birth in 1970, came under threat.

“When I heard that the Independence Stele would be placed in Cosmonaut Park, I thought that Tashkent would lose another iconic place,” said Olga Rakhimova, who set up a Telegram channel to defend the park.

“I made a post about it on Facebook, which Farida Charif shared in her group. In the next few days, people started to gather in the park to support us. We collected over 15,000 signatures for a petition to the president to save the park,” she recalled.

At least for now, Rakhimova’s group has prevailed and Cosmonaut Park has been spared. But Rakhimova and other volunteers continue to monitor the situation in other parks and green zones across the city. Her Telegram and a Facebook page managed by one of her group’s activists have more than 5,000 members combined.

The advantage of informality and the use of the digital space, however, can hardly shield these urban protection groups from the long arm of the state. A month after people gathered to protect Cosmonaut Park in early February this year, for example, new legal measures punishing unauthorised public gatherings with hefty fines and long prison terms were introduced in Uzbekistan.

Likewise, this summer social networks like Twitter were slowed down ostensibly for violating a law that requires servers which process the personal data of Uzbekistani citizens should be located inside the country. In recent years, activists have also experienced problems in accessing Facebook, one of the online platforms most used to spread information and mobilise.

In response, grassroots organisations have developed new forms of smart resistance, such as indirectly publicising their campaigns by setting up events at buildings under threat. For example, various departments at House No. 45 organised fashion exhibitions and a New Year’s Eve Fair, even having it included on a popular list of iconic buildings to visit in Tashkent in 2020.

Tashkent is not alone, as urban transformation has also reached the city of Samarkand, where many of buildings with UNESCO status in the western part of the city – so-called “Russian” or colonial Samarkand – have come under threat. Dmitriy Kostyushkin, a city activist, told openDemocracy that some buildings, such as the city’s first hotel (built between 1900 and 1910), have already been lost to the demolition spree.

Kostyushkin started posting about this on his Facebook account SOS! Save Our Samarkand!. His and other posts on social networks brought the story to the attention of national media, building enough momentum to stop the demolitions.

The story of Samarkand’s University Boulevard is a case in point. Formerly named Abramov Boulevard after a Russian general who laid siege to the city during imperial Russia’s conquest of Central Asia, the Boulevard divides Samarkand between the old 14th century Tamerlane centre and the new city to its West.

Since nobody asked for the residents’ opinion on the boulevard reconstruction, local people mobilised against it. In 2019, Evgeniy Romanenko, a resident, launched the hashtag #ourBoulevard via his popular Facebook group I’m from Samarkand, in order to save it from the local administration’s reconstruction plan. People followed suit on social networks, posting about the historical and even ecological importance of the tree-lined boulevard for the city.

In the end, people’s mobilisation and the ensuing media attention, along with grassroots support from Tashkent, pushed the Ministry of Culture to submit an appeal to the General Prosecutor’s office. The reconstruction plan was stopped in the nick of time.

Other interventions came too late, however, as developers continued to turn Samarkand’s old city into a building site. For instance, the courtyard of a house of a famous painter, Pavel Benkov, who documented 20th century Uzbekistan, has disappeared. Before activists managed to stop the works, the courtyard had been turned into a four-metre-deep pit.

The latest official figures speak of over 80 illicit demolitions carried out across Uzbekistan in 2020 alone, while 55% of former owners weren’t paid any compensation. This makes for fertile ground for protests

While solidarity between cities surfaced in some disputes, like the one over Abramov Boulevard, it is still a rare phenomenon. “There are groups in other cities, but their content is very broad, from social grievances to funny pictures,” said Romanenko from the “I’m from Samarkand” group. “We rarely cooperate,” he added.

Moreover, grassroots movements and organisations in cities other than Tashkent and Samarkand remain embryonic and largely disorganised, despite the fact that urban transformation continues apace across Uzbekistan, from Fergana in the far east of the country to the city of Nukus in its far west. In 2019, dozens of families were forced to leave their homes in Fergana city centre, when construction began on luxury apartments. One resident reportedly died due to the stress caused by the situation.

The latest official figures speak of over 80 illicit demolitions carried out across Uzbekistan in 2020 alone, while 55% of former owners weren’t paid any compensation. This makes for fertile ground for protests. The Oxus Society estimates that, in the first half of 2021, more than half of the 119 protests that took place in Uzbekistan were connected to “illegal construction projects, land grabbing and destruction of property as part of urban regeneration”.

While grassroots activism can claim some victories, including the General Prosecutor’s office new Telegram bot that enables people to report unlawful development and increased penalties for land grabbing for building projects, the fight against rampant urban development is an uphill battle. If anything, the successful case of Tashkent’s House No. 45 shows that, for the future, collaboration and solidarity will be key.

Source: How Uzbekistan’s rampant development is prompting a grassroots rebellion | openDemocracy

Все права защищены. При использвании материалов ссылка на сайт обязательна.