Do international financial institutions sponsor forced evictions in Uzbekistan?

13.01.2025Land Home Justice (Yer Uy Adolat) is a coalition of academics, civil society professionals and activists fighting to end forced evictions and illegal land grabbing in Uzbekistan. Since 2021, Land Home Justice has been jointly investigating, documenting and conducting advocacy on urban land seizures and forced evictions in Uzbekistan, building on our members’ prior individual efforts.

The new report of the network LAND HOME JUSTICE presents the findings of 6 years of investigative research involving interviews, trial monitoring and extensive documentary research by members of the Land Home Justice network: ‘A False Sense of Legality: Compulsory Property Seizure, Land Grabbing And Forced Eviction In Uzbekistan’ (Centre for Public Administration of the Ulster University, December,2024).

The report also investigates the involvement of international financial institutions in this process, using the case of Niyozbek Yuli as an example.

The compulsory acquisition

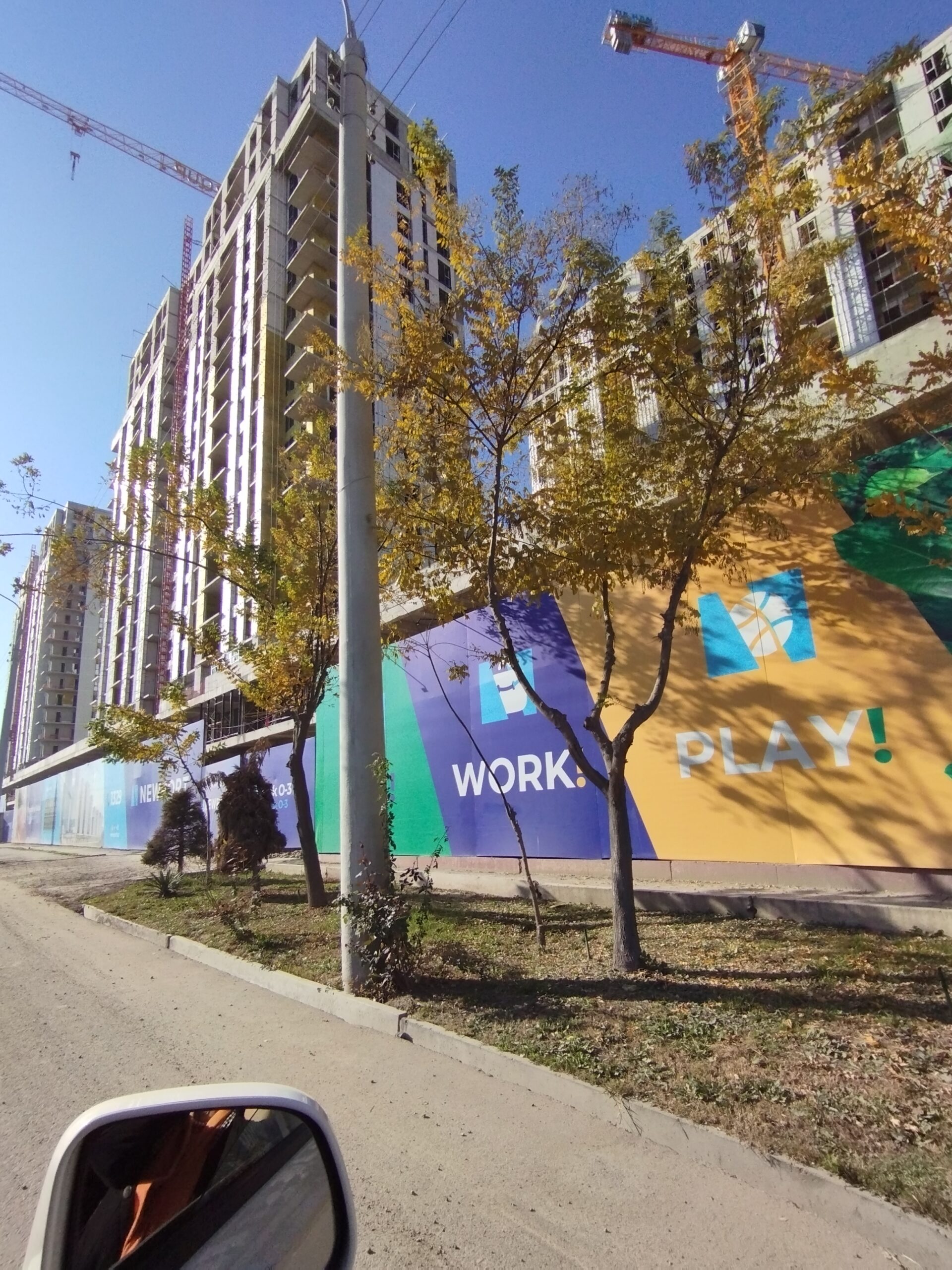

Set among Tashkent’s fashionable bars, sushi restaurants, hotels and embassies is leafy Niyozbek Yuli Street. With its close proximity to the subway, shopping districts and city centre, it is a key target for developers looking to build upmarket residential complexes, hotels and shopping centres.

On 21 November 2017, the Tashkent City hokim issued decree no. 1544. It is notable for four things. First, it orders the eviction of residents living on demarcated land plots along Niyozbek Yuli, Sharofobod, Malyasova and Lashkarbegi streets.

Image: Proposed Nur development , Source: Namuna Development Website

Second, it proposes to incorporate the 10.4 hectares of freed land into the city of Tashkent reserve fund and then reallocate the ‘vacated’ land to a private developer, Steel Quality Business, for permanent use.

Third, Steel Quality Business is given responsibility for compensating residential and non-residential property owners impacted by the eviction, and then completing a demolition exercise.

Fourth, the hokim does not cite any legal authority that would provide grounds for curbing the private property rights of homeowners and businesses. The decision is anchored by the hokim in articles 5 and 10 of the law On Local Government Authority, and the Cabinet of Ministers regulation dated 29 May 2006, On Approval of the Procedure for Compensation of Damage Caused to Citizens and Legal Entities in Connection with the Confiscation of Land Plots for State and Public Needs.

Article 10 of the law on local government authority states: ‘The hokim of the province and the city of Tashkent have the right to grant permanent use of land plots and to terminate the right to own and use land in cases provided for by law.

The other ‘law’ relied upon by the hokim of Tashkent – contained in Cabinet of Ministers resolution no. 97 dated 29 May 2006 – is a by-law. It does not appear to provide the grounds, therefore, to override private property rights set out in legislation with superior status. Furthermore, this by-law only permits the compulsory acquisition of landed property by the state for a number of circumscribed public purposes . No enumerated public purpose is cited in the mayoral decree. Furthermore, none of the public needs set out in the by-law are cognate with what decree no.1544 proposes, which involves the forfeiture of private property and its reallocation to a private company for a real estate development. In addition, under article 23 of the Land Code, before land can be allocated it must first be acquired by the state and registered as state property in the land reserve fund before it can then be auctioned or allocated to a private developer.

This is confirmed by the Deputy Minister of Justice, Aktam Mukhammadiev, in a 2022 letter to impacted residents. Mukhammadiev observes: “In particular, firstly, the decision [no. 1544] does not provide for the [lawful] seizure of the land plot, and secondly, it is impossible to provide (sell) a land plot that is in possession, use, lease and ownership without its seizure (redemption) in the prescribed manner.” The letter recounts the circumscribed bases upon which acquisition for public need can be actioned by the hokimiyat (Tashkent City municipality).

Deputy Minister Mukhammadiev then notes that under the law applicable at the time this decree was passed, it was incumbent upon the Tashkent hokim to:

(1) inform the developer that the land plots could not be provided owing to prior private ownership; and

(2) to offer the developer alternative, available, land plots. (See: article 12 of the Cabinet of Ministers decree no. 54, 25 February 2013,) .

As a result, the letter notes: “Due to the fact that the decision of the hokim of the city of Tashkent dated November 21, 2017 No. 1544 does not provide for the [lawful] withdrawal of a land plot, there are no legal grounds for negotiations related to compensation for damage caused to owners in connection with the withdrawal of a land plot for state and public needs.”

The legal opinion provided to impacted residents by the Deputy Minister of Justice is supported by further advice given by the Secretariat of Uzbekistan’s Human Rights Ombudsman. The Secretariat states: ‘It is known that according to Article 53 of the Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan, private property is inviolable and under state protection, like other forms of property. It is established that the owner can be deprived of his property only in the cases and according to the law. Since the decision of the hokim of Tashkent City No. 1544 of November 21, 2017 does not provide [a basis] for confiscation of the land, there are no legal grounds for negotiating compensation for the damage caused to the owners.’

The Ombudsman adds: ‘Also, based on Article 11 of the Housing Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan, privately owned houses and apartments may not be seized, and the owner may not be deprived of the property rights to the house or apartment, except for the cases specified by law.’ The next section examines the developer and proposed development.

The developer and development

The 10.4 hectares of land identified in decree no. 1544 was assigned to the private company Steel Quality Business. Steel Quality Business is also known by the brand name Namuma Development. News reporting from the period stated that the company intends to initiate a major residential complex on the land featuring 30 buildings and 932 apartments, known as Nur residential complex.

Steel Quality Business was incorporated in Uzbekistan on 1 January 2017. Its company record on the unified register of legal entities was first accessed by the authors on 26 June 2020. Its stated business is ‘services of hair salons and beauty salons’. Steel Quality Business’ statutory fund totalled US$5,700. The initial shareholders are Agzamov Sanjar Nigmatovich (50%) and Husanov Abdullatif Abdugapurovich (50%). The company’s head is listed as Yusupov Umidjan Nigmatovich. Subsequently, the shareholdings in Steel Quality Business changed.

A company extract accessed on 12 April 2022 states that the shareholdings of Agzamov and Husanov had been reduced to 19.4%, respectively, with the majority shareholder now being a limited liability company, Technological Generation. The sole shareholder of Technological Generation at this time was Rolan Sakenov. Later in 2022, the shares held by Rolan Sakenov were transferred to Kim Irina Vladislavovna.

Further information on Steel Quality Business’ shareholders is set out in Table 2

Table 2: Market intelligence on Steel Quality Business shareholders

| Shareholder | Market Intelligence |

| AGZAMOV Sanjar Nigmatovich | When records were checked in 2022, the name Agzamov Sanjar Nigmatovich was listed as the head of Unit Great Trade LLC, an entity 100% owned by Leading Force Company, which specialises in polymer bags, concrete and construction.

Leading Force Company’s primary shareholder is listed as ICS Establishment. It is registered in Liechtenstein where shareholdings and UBO (ultimate beneficial owner) information are not publicly available. Leading Force Company received a letter of thanks from the chairman of Ipak Yuli Bank in 2007, following a successful loan agreement funded with a credit line purportedly issued by the German state’s KfV Bank. KfV Bank is a shareholder in the Uzbekistani Ipak Yuli Bank through its subsidiary Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft mbH. As will be noted shortly, Ipak Yuli Bank has helped finance the Steel Quality Business real estate project |

| HUSANOV Abdullatif Abdugapurovich | When checked in 2023, Husanov was listed as a deputy director at the company Alfa Invest Insurance, which was previously known as Alfa Invest.

Husanov has served on the supervisory board of Zamon Plus Sarmoya. Both Alfa Invest and Zamon Plus Sarmoya have held significant shareholdings in Ipak Yuli Bank. For example, in August 2020 the shareholders of Ipak Yuli Bank included Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft mbH (12%), Triodos Microfinance Fund (12%), UzbekInvest National Export-Import Insurance Co. (8.43%), Zamon Plus Sarmoya (10.92%), Alfa Invest (14.87%), Kafolat State Joint Stock Insurance Company (7.11%), Mebel Invest Group (4.36%) and the Asian Development Bank (4.54%). |

| Technological Generation | A previous 100% shareholder is ‘Sakenov Rolan’ and the current 100% shareholder is listed as ‘Kim Irina Vladislavovna’. It is reported that in 2020 Sakenov took up a senior executive role at Alfa Invest Insurance. |

Steel Quality Business’ registered address when checked on 26 June 2020

Steel Quality Business’ registered address when checked on 26 June 2020

It is apparent that two individuals (Husanov and Sakenov) who have directly or indirectly held shares in Steel Quality Business have executive ties to Alfa Invest (Sakenov/Husanov) and Zamon Plus Sarmoya (Husanov). Both companies, in turn, have held significant shareholdings in Ipak Yuli Bank, which has helped to finance the Nur development.

Moreover, when Steel Quality Business’ record was first checked in 2020, its registered address was the same as that of Alfa Insurance, a subsidiary of Alfa Invest Insurance, a company that has held shares in Ipak Yuli Bank. Given that professional nominees are frequently and lawfully used in Uzbekistan, often drawn from the corporate group’s managerial team, it is unclear if the shareholders cited above are the ultimate beneficial owners of Steel Quality Business, or are instead acting as professional nominees for a third party or third parties. Nevertheless, it does appear from the corporate filings that Steel Quality Business, Alfa Invest and Ipak Yuli Bank are interlinked companies. Requests for comment were sent to Steel Quality Business and Ipak Yuli Bank. No reply was received.

Resident opposition

Residents affected by decree no. 1544 claim that they were notified by a deputy hokim (deputy mayor) of the government’s decision to demolish their homes at a meeting convened in 2018. According to witnesses, the deputy hokim left before residents could ask questions. A resident and former chairman of a mahalla (local council) in the affected area, Fathulla Tashpulatov, 24 April 2022, states:

We gathered at School 17 in our mahalla in the hope of asking the deputy hokim the questions that were bothering us and to discuss how to properly address issues in the paperwork. We wanted to consult with him and discuss all the demolition cases. The meeting was attended by deputy hokim, but no one from the construction company came. The fact is that the officials came to the meeting but did not hear the problems of the people. They came and read their decision, announced the demolition of the houses, and left without hearing anyone. What does that mean? Why did he gather the people there? If they don’t want to listen to the people, why did they gather us? The population is still suffering.

Testimony collected by the monitors 10 March 2021confirms that some residents were opposed to the proposed development and were unsatisfied with the compensation offered by the developer.

One example is local resident Farida Langer. Farida Langer’s home was situated in passage 4, off Niyozbek Yuli Street. She enjoyed lifetime inheritable possession over the land plot on which her home was built.

She lived there with her children and grandchildren. The latter attended local schools. Langer was unhappy with the compensation proposal as she believed none of the alternatives offered were adequate or commensurate with what was being taken away.

Under Uzbekistani law, Langer was within her rights to retain her private property and residence. Nevertheless, she was informed by the developer Steel Quality Business in a letter dated 22 December 2020: ‘According to the decision of the hokim of Tashkent City No. 1544, dated 21 November 2017, the private company “Steel Quality Business” was allocated a land plot between Yunusobod and Mirzo Ulugbek districts, from Sharofobod street to Malasova and Niyozbek streets to Lashkarbegi street for the construction of a multi-storey residential complex.’

The letter continues: ‘This decision of the hokim of Tashkent provides for the demolition of residential and non-residential premises located in this area with the provision of compensation to owners.’ Langer was informed that she may either accept US$40,000 compensation, purchase of an apartment on the secondary market or provision of a new apartment from the Nur complex. She was also advised: ‘If you refuse or do not provide a response within the specified period, we will be forced to appeal to the court with the appropriate claims.’ In the subsequent statement of claim filed against Langer by Steel Quality Business, decree no. 1544 is again cited as the basis for the company’s title over the property and right to evict residents with compensation.

The company also cites article 47 of regulations contained in an appendix to Cabinet of Ministers decree no. 911 “About Additional Measures to Ensure the Guarantees of Property Rights of Physical and Legal Entities and to Improve the Procedure for Expropriation and Compensation of Land Plots”, dated 16 November 2019

The specific article states: ‘When written consent is obtained from 75% of the owners of the real estate objects located on the plot of land that is planned to be withdrawn (when the agreement is concluded), but if it is not possible to obtain the consent of the remaining owners (when no agreement is reached), the initiator has the right to apply to the court with a claim for the compulsory purchase of their real estate objects. In this case, the amount, types and terms of compensation to be given to the owners who did not agree (agreement was not reached) shall be determined by the court procedure.’

This provision applies to a land plot containing multiple residential properties. Langer’s home was part of a one-storey housing complex built during the early Soviet period. Therefore, the developer appears to have been arguing that other residents in the complex had consented, rendering Langer a minority who could be compelled to sell her property by the court.

Steel Quality Business asked the court to order Langer to accept compensation and vacate her home. In an interim decision, the court did not review the legality of the process through which the developer obtained title.

Nor did it consider in its judgement the argument regarding the grounds for removal of Ms Langer from her home. The interim decision did, however, specify that an independent valuer should evaluate the value of Langer’s home and report back to the court.

Langer recalls:

‘I was taken to court. How nervous. My leg hurts, and sometimes my blood pressure goes up. I am not young, I am 66 years old. I didn’t ask them for much. I asked them to compensate me for the total area of my house. My grandson has been attending schools here since first grade. Now he is in seventh grade. So I asked them to give me a one-bedroom apartment and my children a two-bedroom apartment. I didn’t ask them for anything stupid.’

The case against Langer was subsequently dropped by Steel Quality Business. She decided to accept the compensation and left her home.

A second case involves Tashkent resident Alieva Shakhzade. Shakhzade had lived on Niyozbek Yuli Street since 1981.

Shakhzade built a new home on the site in 2010, which she lived in with her daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter. Shakhzade was the first resident to challenge the legality of the hokim’s 2017 decision to grant the land to Steel Quality Business, with assistance from her son-in-law Javlon Mahmudov. As it had with Farida Langer, Steel Quality Business initiated legal action to evict Ms Shakhzade and her family, with compensation.

Steel Quality Business again relied on decree no. 1544 as the lawful basis for its title and the right to evict existing home owners in the area with compensation. The court characterised this decree as granting seizure of a land plot for public need – despite the fact that no such need was expressed in the decree – and as a result argued that article 27 of the Housing Code applied, requiring compensation be paid.

Steel Quality Business claimed that it offered compensation in the form of ‘the acquisition on the secondary market at the expense of the developer of another equivalent well-equipped residential premises at the choice of the defendant, [or] the payment of monetary compensation in the amount of 70,000 US dollars in national currency at the exchange rate of the Central Bank of the Republic of Uzbekistan on the day of payment, [or] providing an apartment with total usable area equal to the demolished house’. .

The judgement notes: ‘However, the defendant did not agree to any of the proposed options, deliberately preventing the demolition and delaying the construction.’ Judge Kariev ordered the eviction of Alieva Shakhzade and her family and ordered Steel Quality Business to pay UZS1.316 billion in compensation.

The court also questioned the legality of the 2010 home reconstruction on the property and Shakhzade’s overall title to the land. It was alleged to the court by a representative of the Yunusabad District Hokimiyat that the 2010 reconstruction was done illegally and that their home was an unauthorized building, an assessment that the court appears to have accepted. It appears that the state potentially used this claim to weaken the resistance of Shakhzade. However, in this instance, Shakhzade and her family contested the initiating decree no. 1544 in the Tashkent Administrative Court .

The Administrative Court remarked that under articles 2 and 13 of the then applicable regulation, acquisition for public need required the consent of the landowner.

The compensation arrangement should have been agreed in advance of the mayoral decree and information relating to the owners of residential and non-residential premises and the compensation to be paid to them, ought to have been enumerated in the decision of the hokim, the court observed. It was also noted that under regulations set out in the Cabinet of Ministers decree no. 54, (dated 25 February 2013 and expired on 1 July 2018 ), provision for the use of land owned, used or leased by an individual can only take place after it has been seized in the prescribed manner by state authorities.

In addition, the court noted, under the regulations the decision must be made in compliance with urban master plans. The court then remarked with respect to these above regulations, ‘in the adoption of this decision [decree no. 1544], the requirements of the above laws were not followed [by the mayoral administration], and as a result, it seems that the private enterprise built structures that violated the requirements of the law’.

Attention was also drawn by the Administrative Court to relevant articles of the Urban Planning Code, which requires that proposed developments be the subject of open discussion with citizens, with all relevant information disclosed on the project impacts.

It was noted that the Tashkent City administration had failed to notify affected residents in the prescribed written format at least six months prior to the proposed demolition. With regard to procedural irregularities, it was further observed by the court that decree no. 1544 was issued without prior approval from the Tashkent City Council of People’s Deputies.

With respect to statute of limitations, the court remarked that under article 186 of the Code on Administrative Proceedings, public decisions must be challenged within three months of the interested person becoming aware of the violation of their rights, freedoms and legal interests.

The court was satisfied that the plaintiff only became aware of the violations in June 2022, and thus had acted within the stipulated three months. In light of the violations noted above, the court invalidated decree no. 1544 as it applied to the property of Shakhzade.

While a rare legal victory for an impacted resident, the judgement also highlighted the precarity of private property rights. Where the right has been taken away by government decision, action must be taken within three months of the affected person becoming aware of the rights violation. Second, the Administrative Court’s decision on the illegality of the decree only applies to the property of the petitioning plaintiff; the deemed illegal decision is allowed to be enforced against all other affected peoples. Third, it also rests on plaintiffs being able to prove property rights, drawing on the information systems and personnel of the body accused of violating those property rights.

An appeal was lodged against the Administrative Court decision by the developer Steel Quality Business.

A hearing was convened without Shakhzade’s representative being present (her son in law), with the court claiming he had been duly warned. The court ruled that under article 1 of regulations contained in the governmental decree no. 54, 25.02.2013 , (cited in the lower court decision) – which requires state authorities to first seize land in accordance with the law and master plans – the relevant due process requirements did not extend to the construction of objects located on the territory of two or more districts or regions. Because decree no. 1544 related to land spread across two Tashkent districts, the regulations were ruled by the court not to apply. This appears to be a misreading of the regulations. The regulations state that the rules applicable for land plots across two or more districts are set out in Appendix No. 2 , which echo the rules applicable to land plots in a single district.

Table 3: A comparison of the regulatory requirements set out in decree no. 54 , 25.02.2013

| Appendix 1 | Appendix 2 |

| 4. Provision for town-planning activities of a land plot owned, used, leased or owned by legal entities or individuals is made only after the seizure (purchase) of this land plot from them in the prescribed manner. The decision to seize a land plot and demolish residential buildings, other buildings, structures or plantations is made in accordance with master plans, as well as detailed planning and development projects for residential areas and micro districts of settlements. | 4. Provision for non-agricultural needs of a land plot owned, used, leased or owned by legal entities or individuals is made only after the seizure (purchase) of this land plot from them in the prescribed manner.

7. It is prohibited to provide land plots without urban planning documentation, except for the cases provided for by this Regulation. [Part II sets out procedures for granting land plots in the absence of urban planning documentation.] 11. In cases of receipt from legal entities and individuals of an application for the provision of land plots occupied by buildings and structures, the rights to which are registered for other individuals and legal entities in the manner prescribed by law, the applicant is sent a notification about the impossibility of providing the requested land plot, with a proposal to independently redeem the immovable property from the owners or other options for choosing free land plots. |

It was also stated by the court that ‘there are no documents confirming the right to the land plot occupied by this house and adjacent to it’. Referring to the civil court decisions, the Appeal Administrative Court noted that Shakhzade will be paid compensation for her demolished home. As a result, it argued, there is no rights violation by decree no. 1544.

Finally the court also ruled that Shakhzade learnt of decree no. 1544 in December 2020, and thus failed to appeal to the courts within the required three months. As a result of these conclusions, the initial decision of the Tashkent City Administrative Court was annulled. The Shakhzade family, facing considerable stress, strain and financial resourcing challenges, finally elected to accept compensation and leave their family home.

The cases of Langer and Shakhzade demonstrate the significant challenges that residents face when seeking remedy after their real property has been appropriated through an illegally rendered decision and handed over to a private developer. First, while the illegal nature of the decision may be attested to by accountability bodies, such as the Ombudsman and Prosecutor General, these views have no legal force.

Affected residents must go to court. Second, when prosecuting their claim in court, residents have a limited window of three months to initiate their action against private property right violations by the state. In effect, this meant that for residents along Niyozbek Yuli Street their constitutionally and lawfully defined property rights would expire if they failed to challenge in court an offending decree within three months from the date they learnt of the decree’s passage. Third, as the appeal judgement in the Shakhzade case demonstrates, the courts appear to make explicitly wrong statements of law, which undermine the rights of residents. Fourth, even in the rare circumstance where a plaintiff overturns an illegal decree, the judgement is a partial ruling applicable to their property only. Fifth, when residents face civil litigation, the courts accept without review the legality of potentially illegal decrees, and decide the case only on the basis of the relevant compensation procedure.

This helps to also situate other significant challenges facing residents affected by property confiscations and evictions. Few have the resources to pursue litigation, especially given the widely held view in Uzbekistan that the court system works in favour of government parties and developers. Second, residents face pressure to accept compensation, or face court, a forum in which many lack faith. As a result, residents are therefore under significant pressure to accept violations of their private property rights by the state and seek whatever compensation they can from developers.

According to Fathulla Tashpulatov, who is a resident and a former chairman of a mahalla in the area affected by the Nur complex, this totality of forces creates a disparity of power when negotiating compensation. He claims:

‘The company’s appraisal of the house was also not fair. They underestimate the total area of the house and offer very little compensation. They are doing what is convenient for them. The company has two realtors and one employee in its office … Now a realtor named Rustam has come … He often comes and makes us nervous. He is pressuring us to move faster. He threatens to take us to court and deprive us of our private property rights if we do not agree to these terms [of compensation].’

Other residents in the affected area echo Tashpulatov’s view, arguing that they have been pressured to leave and are not satisfied with the proposed compensation. Exacerbating matters, residents also claim that the surrounding construction work being undertaken by Steel Quality Business caused disruption to essential services, such as water, gas and electricity, which added to the pressure on them.

In the latter respect, it is important to recognize the difference between the value of a property to a homeowner and the market value of a property. For residents, a home represents memories, community connections, personal security, job security, access to services, access to friends and family – in addition to being a financial asset. On the other hand, the compensation paid for compulsorily acquired homes is ostensibly based on market value, which does not price in these factors of significant value to impacted residents.

While residents contest that compensation is fairly determined even by market standards, it needs also to be underlined that market standards fail to recognize the full loss experienced by impacted residents. In the case of the Nur residential complex, the authors were able to identify a source of finance used by Steel Quality Business to fund the project, a fact that is ordinarily not disclosed by developers or banks. This provided an opportunity to assess how institutions involved in the financing of property developments assess risks associated with forced evictions.

The role of financial institutions

The Nur complex has received financing from Ipak Yuli Bank (IYB), which raises additional governance questions. The loan capital was provided to Steel Quality Business for the Nur complex project. It has been noted already that two individuals (Husanov and Sakenov) who have directly or indirectly held shares in Steel Quality Business also have ties to Alfa Invest and Zamon Plus Sarmoya. Both companies, in turn, have held significant shareholdings in IYB.

Furthermore, when Steel Quality Business’ record was first checked in 2020, its registered address was the same as Alfa Insurance, a subsidiary of Alfa Invest Insurance, a company that has held shares in IYB. This provided evidence to indicate that there were direct ties between the developer and the bank’s shareholders. Other shareholders in IYB include a number of international investors, notably the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the German development bank, Deutsche Investitions- und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG).

A series of questions were sent to the ADB and DEG by the authors regarding the finance of Nur complex. In response to these questions, the ADB stated: ‘We were informed by Ipak Yuli Bank (“IYB” or “the Bank”) that in September 2020, the Bank provided a loan to Steel Quality Business for the construction of multi-story apartment buildings within the Stage 1 (Block A) of the NUR Project (Namuna Development) (the “Loan”).’

The ADB also advised: ‘IYB confirmed to us that prior to the approval of the Loan, IYB screened it against ADB’s prohibited investment activities list, and categorized the project in line with its environmental and social management system (ESMS) … We were informed by IYB that they undertook due diligence and confirmed that former residents of Block A were compensated by Steel Quality Business in 2020. IYB further confirmed that they did not receive any information about any disputes regarding the part of the NUR project which was financed by the Bank. In September 2022, Steel Quality Business repaid the Loan.’

In a subsequent letter, the ADB provided further information on the due diligence conducted by IYB. They advised:

Ipak Yuli Bank has adopted and implemented an environmental and social management system (ESMS). Under this ESMS, projects are screened for potential involuntary resettlements and the impacts thereof; in addition, further due diligence procedures are carried out. Ipak Yuli has informed ADB that during the due diligence of the construction project of Block A Phase-1, they have reviewed documents certifying the rights of the developer, i.e., Steel Quality Business (SQB), with respect to the territory comprising the land plot of Block A Phase-1. SQB provided IYB a cadastral register dated 28 March 2019, showing that the land was legally in their possession. In addition, IYB also took comfort in the fact that at the time of the due diligence, empty private houses were observed on the territory of Block A. Documents, which had been reviewed by Ipak Yuli, confirmed that agreements with respect to the transfer of property had been entered into between the parties and that cash proceeds were received by the former owners of these private houses. Based on the findings of this due diligence, namely that the owners of the houses had vacated the premises and transferred the title documents to the developer after having received cash proceeds from the same, Ipak Yuli concluded that mutual agreements had been reached between the owners of houses in Block A and the developer and that there were no outstanding compensation matters.

It was also noted that: ‘At the time of the assessment and due diligence of the loan application, permits and licenses received by the borrower for the construction of the residential complex of Block A were reviewed by IYB, including the decision of the hokim to allocate a site for the construction of a residential complex, together with further architectural and design documents.’

When asked about the corporate ties between Steel Quality Business and IYB shareholders, the ADB originally advised ‘IYB also confirmed that they have no affiliation with Steel Quality Business apart from being a client of the Bank’.

In further correspondence, the ADB noted that the shared address between Steel Quality Business (SQB) and Alfa Insurance, according to IYB, was the result of a leasing arrangement:

‘At the time of the assessment of the loan, SQB, among other documents, provided a copy of the lease agreement, according to which the company accepts the premises for temporary use as an office. The address of the leased premises is indicated in Tashkent, Yashnabad district, S. Azimov and Tarrakiyet streets, the lessor is SO DHO “ALFA LIFE”.’

Alfa Life, it should be noted, according to a company extract from 2020, was during this period 100% owned by Alfa Invest, while Alfa Invest in turn was a shareholder in IYB.

IYB also advised the ADB that Abdulatif Husanov was not an executive at Alfa Invest when the loan was entered: ‘As for the position of Abdulatif Husanov, who is currently the Deputy General Director for IC ALFA INVEST JSC, in accordance with the information provided on the company’s website and the information received by IYB from IC ALFA INVEST JSC, at the time of examination of the client’s documents by IYB, Mr. Husanov was not part of the management team in the insurance company.’

To summarise then, it appears from the information contained in this response from the ADB, that IYB had sight of decree no. 1544, but did not identify the potential illegalities referenced by the Deputy Justice Minister and Administrative Court of first instance, which summarises the applicable law at the time the decree was passed. IYB states that it accepted vacant houses, signed compensation agreements and transfers of title as evidence that the properties had been acquired by consent from previous owners.

Furthermore, it appears that IYB shareholder the ADB accepts the statement from IYB that the connections between Steel Quality Business and its other shareholders were a matter of coincidence, and not indicative of a transaction between affiliated parties. It appears to be IYB’s contention that by coincidence Steel Quality Business leased a property from the Alfa Invest subsidiary, and it was also only by chance that one of Steel Quality Business’ shareholders would go on to be a senior executive at Alfa Invest. However, Abdullatif Husanov, in addition to being an executive at Alfa Invest, previously served on the board of IYB shareholder Zamon Plus Sarmoya, dating back to at least 2017. This suggests that Husanov indeed has a prior executive relationship with an IYB shareholder that precedes the loan.

While it is not being asserted that any of the private parties involved in this development were engaged in illegal activity, the evidence does point to concerning weaknesses in the due diligence conducted by IYB. In particular, IYB failed to identify serious legal shortcomings in the state-initiated property confiscation and forced eviction exercise. It is also concerning that IYB denies any affiliation with Steel Quality Business beyond the loan arrangement, despite multiple links between its shareholders and Steel Quality Business. It is also troubling that the ADB appears to have accepted this explanation solicited from IYB.

Both IYB and Steel Quality Business were given the chance to comment on the claims made by residents and associated report findings, but no response was received.

Conclusion

The Niyozbek Yuli Street case points to a number of factors that will be evident in other case studies presented in this report. The first factor is the compulsory acquisition of privately owned homes by the state through orders that have no apparent lawful basis, in order to facilitate private real estate developments. Second, there is the violation of resident property and human rights by public authorities. Third, weaknesses in the court system means that, in effect, residents lack access to a meaningful remedy, despite receiving notional support from state agencies with oversight duties for law and justice. Fourth, residents are under significant pressure to accept compensation, with pressure coming from both state authorities and developers. Fifth, compensation fails to fully recognise the losses suffered by residents. Sixth, third parties helping to facilitate private development are not effectively identifying risks of improper process before providing support to projects impacted by forced eviction and compulsory property acquisition.

Recommendations to the International Financial Institutions

International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Finance Corporation are directly and substantively involved in both supporting and financing urban redevelopment and the modernization of agribusiness in Uzbekistan. It is therefore critical that they act immediately to support steps that can address the issues documented in this report. As significant influencers of policy in Uzbekistan, IFIs play a material role in the country’s development through finance, while their symbolic role serves as a bulwark for investor confidence.

Set against this backdrop and the findings presented in this report, it is recommended that IFI’s:

a) Recognise in their risk assessments the high likelihood that state-organised acquisitions of private property and farm land in Uzbekistan will result in human rights violations, unlawful conduct and the abuse of public power.

b) Support and engage with the recommendations in particular:

- Develop enhanced due diligence that identifies red flags for human rights violations, and abuses of official power. Desist from investing in projects before thorough risk assessment and effective mitigation measures have been implemented.

- Conduct retroactive risk assessment of all projects linked to illegal land expropriations, including “voluntary” land lease terminations, and forced evictions documented in this report and immediately suspend loan disbursement to projects until effective mitigation strategies have been implemented and remedy for victims has been provided.

- Commit to undertake regular, independent monitoring of high-risk development projects that reflects a rights-based approach and meaningful stakeholder engagement.

- Given the persistent restrictions on freedoms of expression and association, IFIs should develop effective strategies to ensure meaningful stakeholder engagement and ensure the ability of project-affected parties to speak out or voice their concerns without fear of reprisal.

c) Where IFI financing has had a material role in enabling human rights abuses resulting in violations of private property and land rights, implement concrete measures to provide victims with a remedy.

d) Work proactively with victims, civil society actors and domestic and international experts in order to build policies and procedures into development finance that can rigorously address risks in Uzbekistan, such as those highlighted in this report.

e) Premise future investments in urban development and sectors such as agriculture, mining and renewable energy where land acquisitions are foreseen on a multi-stakeholder-led roadmap of reforms that will progressively address the risk factors identified in this report and other cognate research.